It’s kind of fashionable to write off Catholic priests as reactionaries and/or child molesters and/or hypocrites. And doubtless there are many priests who fit into one or more of those categories. Chris Ponnet, though was not one of them.

It’s kind of fashionable to write off Catholic priests as reactionaries and/or child molesters and/or hypocrites. And doubtless there are many priests who fit into one or more of those categories. Chris Ponnet, though was not one of them.

I first met him on a Sunday morning in 1990 when I went to a Mass at Our Lady of the Assumption church in Claremont, California. After the Mass, I approached him and said to him, “hello, I’d like to become Catholic.”¹ We made an appointment for me to talk with him further, and that was the beginning of a friendship that lasted decades.

I didn’t know at the time how new of a priest he was at that time. OLA was his second parish assignment after ordination which was less than seven years previous. He seemed so wise and fully formed and he was a fount of wisdom. In the year that followed, I finished my last semester of college, started my first grown-up job, and watched as the US went to war in Iraq with questionable motivation. Chris was active in the anti-war movement and during Lent in 1991, he undertook a 40 day liquid-only fast that ended on the day of a protest march in Pasadena where he was pushed in a wheelchair, too weak from the fast to be able to march with the others.

Anti-war was not his only stance in the margins. He also was responsible for OLA having a ministry to gay and lesbian Catholics, and had been active in ministering to those with HIV and AIDS since before he came to OLA. He was a vigorous opponent of the death penalty (something that, from my reading of the Sermon on the Mount, seemed like it should be standard for all Christians).

While still in his 30s, Chris had his first heart surgery, a quadruple bypass. Heart problems were a deadly killer in his family. He had lost his father and one brother to bad hearts already at this time and his heart would be his eventual killer, but when he returned from the hospital, he was in cheerful spirits. I remember asking him about his heart surgery scar and he cheerfully unbuttoned his shirt to show it off before saying that the really nasty scar was the one on his leg where they took out a vein to use for the bypass and he rolled up a trouser leg to show off that scar as well.

Surprisingly, he wasn’t the person who brought me to the Los Angeles Catholic Worker—that was the consequence of my driving a group of confirmation students there on a Wednesday night for their confirmation service project.² Only after I started going regularly did I discover that he was the regular celebrant for the Wednesday evening liturgy and potluck on the first Wednesday of each month. I remember carpooling with him once³. We met at the church office and he said, “let me just change really quick before we go.” He had been wearing the standard black shirt white collar clerical dress, but he changed out of it into a plaid flannel shirt to celebrate the liturgy at the Catholic Worker.

Not too long after this, his term at Our Lady of the Assumption came to an end (it’s standard in the modern church to move priests from one assignment to the next every six years, with the occasional six-year renewal for those in a pastor position). His new assignment was pastor of the Saint Camillus chapel at L.A. County Hospital, a small little church across the street from the hospital where attendees at the regular Mass were often brought to the chapel in their hospital beds with IV bags attached. I don’t know what the community was like before him, but under his leadership, in addition to the Masses serving the hospital, there was also a monthly (later weekly) peace and justice Mass held in the chapel and he used it as a home base for his own activism, continuing to support the marginalized and poor while fighting for justice.

I’m writing this on the plane back to Chicago after attending his memorial services in Los Angeles: the vigil service on Monday evening and the funeral Mass at the cathedral on Tuesday. The latter was presided over by Archbishop Gonzalez with roughly a hundred priests (including a handful of other bishops and—I think—Cardinal Mahoney) at the Mass.

During the procession, Chris’s religious symbols (chalice, paten, holy oils) and other symbols (photograph, hospital badge, sandals, etc.) were brought forward and placed at the front of the church next to his coffin. The sandals felt especially poignant as it was his footwear of choice (and for a while, in my own admiration and imitation of Chris, my own footwear of choice).

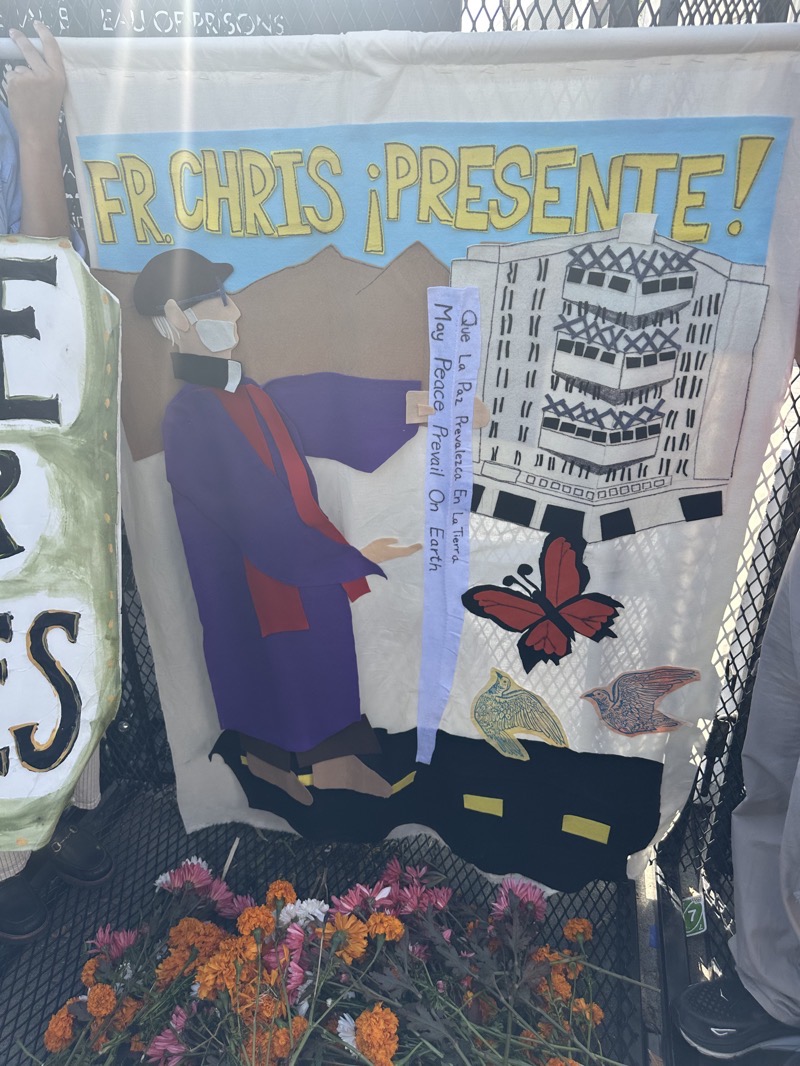

After the Mass, there was a procession to the downtown Federal building and jail where a small march of protest and interfaith vigil was held, a continuation of the regular vigils that Chris participated every Friday. It was reported that before the surgery when he died, he told the doctors to do whatever it took to revive him if anything went wrong because his work wasn’t finished. They were unable to save him so the work falls upon us to complete.

Father Chris Ponnet, ¡Presente!

- The full story here is longer than what’s appropriate for this post, so I’ll leave it at that.

- Yes, that was a direct inspiration for part of “Elijah’s Funeral.”

- Pro tip. If you ever carpool with a priest, do not let him drive. Without exception, every single priest I’ve ever ridden with has been a terrible driver.

Leave a Reply